2nd Battalion, 8th Cavalry Regiment 1967-68

|

|

|

Khe Sanh and A Shau Valley Operations

| General Westmoreland tasked the 1st

Cavalry Division with the combined mission of relieving the besieged US

Marines at Khe Sanh and thereafter conducting a reconnaissance in force in

the A Shau Valley. These large-scale operations were known as Operation

Pegasus and Operation Delaware.

Khe Sanh - Operation Pegasus The relief of the 26th Marine Regiment at Khe Sanh commenced on 1 April. On 21 January, NVA forces had completely surrounded this US Marine Regiment at Khe Sanh with a superior force of three to one. The enemy not only had a significant numerical advantage but they also commanded the initiative by preventing the Marines from conducting offensive operations outside of the base. Despite heavy bombardments by B-52s, tactical air and intensive counter artillery fires, the NVA was able to pound the runway and key installations at Khe Sanh with rockets, artillery and mortars throughout the 66-day siege. On 23 February, for example, the Marines reported receiving over 1,300 incoming rounds. The 1st Cavalry Division’s 3rd Brigade led the attack west by establishing two firebases almost halfway to Khe Sanh, while two battalions of the 1st Marine Regiment conducted a ground attack following Route 9 west toward Khe Sanh. Two days later, the 2nd Brigade landed three battalions southeast of the Khe Sanh base and attacked northwest toward the base. Enemy resistance was considered moderate until units of the 26th Marine Regiment who had been under siege at Khe Sanh for over two months, attacked and secured Hill 471 on 4 April. The following morning at first light, an enemy battalion charged up Hill 471 in a traditional infantry attack. According to the Marines on Hill 471, it was a very one-sided firefight as the attacking NVA forces were mowed-down by a combination of artillery fire, tactical air strikes and automatic fire from the Marine defenders. The mission of our brigade was to continue security of Quang Tri and to conduct operations south and west of the city. On 5 April, the 1st Bn 8th Cav was air assaulted into a LZ Snapper, located south of Khe Sanh and overlooking Route 9. Like the Marines on Hill 471, the 1st Bn 8th Cav was also subjected to an NVA attack on the following morning and once again, the enemy was forced to retreat after suffering high casualties. It is believed that our battalion established a blocking position close to the “Rock Pile”, where the forward battalion command post was subjected to a 122mm rocket attack. The relief of Khe Sanh was effected on 8 April, and the 1st Cavalry Division assumed responsibility for the Khe Sanh base and securing the area. In his concluding remarks on Operation Pegasus, the Commanding General of the 1st Cavalry Division, General Tolson, stated: “In fifteen days, the division had entered the area of operations, defeated the enemy, relieved Khe Sanh, and been extracted from the assault-only to assault again four days later into the heart of the North Vietnamese Army's bastion in the A Shau Valley”. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A Shau Valley - Operation Delaware | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

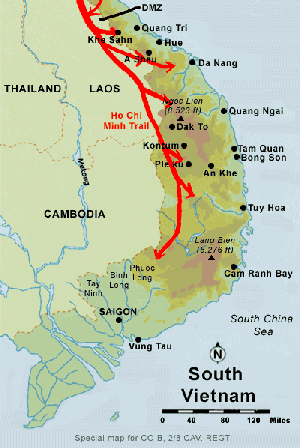

It is important to note that the NVA “initiated” the Battle of Dak To (Nov 67), the Battle of Tam Quan (Dec 67), the siege of Khe Sanh (Jan-Apr 68), and the Tet Offensive (Jan-Apr 68). Now it was our turn to go on the offensive and on 19 April 1968, we “initiated” a large-scale attack on NVA forces in one of their most important jungle sanctuaries, the notorious A Shau Valley. The NVA overran the US Special Forces Camp in A Shau in March 1966, and according to General Tolson, Commanding General of the 1st Cavalry Division: ”The enemy had always considered the A Shau Valley to be his personal real estate and it was a symbol of his relative invulnerability.” For the NVA, the valley became a crucial part of the Ho Chi Minh Trail and served as one of their main points of entry for the infiltration of troops and supplies into the I Corps Tactical Zone. The A Shau Valley is less than ten kilometers from Laos, a country that the NVA exploited as a safe haven for moving troops and supplies into South Vietnam. Because of international law restrictions, US and allied forces were not allowed to engage NVA forces operating in Laos. Consequently, when the NVA bombarded us in the A Shau Valley with rockets and artillery fired from locations in Laos, we were unable to take any form of counteraction to silence their guns. |

HO CHI MINH TRAIL MAP |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thanks to Sven Gerlith | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The A Shau Valley was notorious because it left a lifelong mark on most of us and we have great difficulty explaining why. The most likely explanation was our exposure to many awesome and startling experiences during this violent three-week operation, such as: The shattering explosions from the C-130 Hercules aircraft loaded with ammunition that was shot down close to our position with the loss of all the crewmembers. Being repeatedly shelled by NVA artillery guns from locations in Laos and knowing that our folks were not allowed to return the fire. Constant contacts with enemy forces involving many firefights, ambushes and sniping activity. The large number of our helicopters hit by enemy antiaircraft fire. The disturbing sound of enemy tanks moving at night on the valley floor. While the triple canopy jungle prevented the optimal use of our airmobile capabilities at Dak To, the operational requirement to conserve helicopter fuel created a similar situation during the A Shau Valley operation. To evade enemy antiaircraft fire, our helicopters had to make a high altitude climb over the mountains and then a sharp spiral descent into the A Shau Valley. Conducting combat operations on such a vital stretch of the notorious and dangerous Ho Chi Minh Trail. Tensely watching the sequence after the shooting down of a US Air Force F-105 jet fighter with the ejection of the pilot and his slow descent by parachute to safety. The large quantities of enemy material captured, ranging from sophisticated military equipment to a stock of bikinis. The noise and shock waves generated by B-52 strikes close to our position. Then there was the unknown factor as succinctly stated by Captain John Taylor (Cavalry Magazine, 1968): "The feeling the majority of the men had upon first coming into the valley was a sort of fear; distinctly different from that felt during Hue or Khe Sanh. We had heard so many stories about A Shau... the possibilities of running into large concentrations. We had a fear of the unknown. We thought that just around any corner we would run into a battalion of North Vietnamese." Even the “Dictionary of the Vietnam War” made an attempt to capture some of our extraordinary experiences with this description: “The A Shau Valley was the scene of much fighting throughout the war, and it acquired a fearsome reputation for soldiers on both sides. Being a veteran of A Shau Valley operations became a mark of distinction among combat veterans.” For Bravo Company, the A Shau Valley operation began with a truck convoy from Quang Tri to the large staging area in the vicinity of Camp Evans, the 1st Cavalry Division base camp at Hue-Phu Bai. The following photos show Bravo Company on the way to this staging area. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

DESTROYING CAPTURED NVA EQUIPMENT |

CAPTURED NVA VEHICLES |

CAPTURED NVA 37MM ANTI-AIRCRAFT GUN |

SOME OF THE NVA WEAPONS CAPTURED IN A SHAU |

|

|

|

|

| CHINOOK OFFLOADING AT A SHAU VALLEY LZ | Thirty years after this photo was taken, we discovered that the pilot of this Chinook was Pat Murphy, C/228th Assault Helicopter Battalion, and here is his account from the Battalion website: This was “my ship, Crimson Tide 472, with its butt sitting on the edge of the LZ being unloaded as the front end is hovered. If I had known that this photo was being taken, I would have come out of the bird and posed for this guy.”

|

|

|

Blackfoot was assigned the mission of securing Hill 975 (see above map)

and establishing an observation post to protect the A Luoi Airfield. By

this time the airfield was being prepared to receive C-130 Hercules

landing with supplies of ammunition and food. The airfield was not only

important for aerial re-supply, but also because it was the location for

the tactical operation centers for the 1st Brigade and the 1st

Cavalry Division. Hill 975 overlooked the airfield and if the NVA

controlled it, they could have engaged our aircraft using the airstrip

with direct and indirect fire. Therefore, denying the enemy control over

Hill 975 was very important and Blackfoot established an outpost manned

by a squad at the base of the hill. One of our troopers recalls that

when the platoon reached the top of Hill 975, they were bombarded with

sticks thrown at them by Orangutans. The initial reaction to these

sticks was a belief that the NVA were throwing hand grenades. We also

had to clear a large tree on top of Hill 975 to permit the landing of

choppers and one of our troopers suffered a broken leg when the tree

fell on him. A Blackfoot trooper also remembers observing a NVA attack

on the A Loui Airfield at the engineer sector of the perimeter. He

recalls green tracers going in, red ones going out as the engineers

burnt the barrel out on an M60. “ I can remember the tracers going up,

down and sideways as the barrel flexed.” |

||

A LUOI AIRFIELD WITH HILL 975 ON LEFT |

||

|

The A Shau Valley operation left us with many vivid memories of our experiences. Many troopers remember the shortage of drinking water and some recall a shortage of C-Rations. Apparently we were issued three C-Ration meals on the morning of the air assault and the only re-supply that we received during the following 2-3 days was ammunition. One of our platoons discovered a cache of “NVA rice and we ate that for a couple of days”. We were also desperately short of water and this is what one of our Mohawk troopers remembers about a patrol down the mountain to the valley floor in search of water: “We were loaded with canteens and we found water, but the eerie part of it was that it was at an N.V.A. camp and they had abandoned it quickly before our arrival. Their small fires were still smoldering. We filled our canteens from a piece of bamboo they had driven into the slope of a hill into a spring. Their ingenuity was remarkable. The sight of three smoldering fires had me terrified.”

|

||

|

|

||

|

It is highly likely that Bravo had secured LZ Cecile for a few days and the company was assigned a new mission on 4 May 1968. We departed the LZ with Blackfoot leading the company. Eventually we came to a corrugated (PCP planking) road and discovered a trail running parallel to this road with very fresh foot tracks. As the water was still seeping into these foot tracks, we requested an artillery fire mission on suspected enemy positions and this was denied. As it was a very rare occurrence to receive a denial for an artillery fire mission, this must have been due to a critical shortage of artillery rounds. The enemy had established a well-camouflaged U shaped ambush centered on the road and trail with machine gun positions on the left and right flanks as we approached the ambush site. Fortunately, Blackfoot approached this NVA ambush on two fronts, one close to the road and the other close to the trail, and this caused the enemy to activate the ambush early and to disengage quickly. Two of our troopers were killed during this ambush, David Schultz and our medic, Dempsey Parrott. At least two of our troopers were wounded. We quickly evacuated all of our casualties by “Dust Off” air ambulances. Those who witnessed the crash of the C-130 Hercules in the A Shau Valley will never forget it. It was 1400 hours on 26 April, and we all knew that the C-130 making its approach to air drop ammunition at A Luoi airstrip/ LZ Stallion had been hit by enemy antiaircraft fire and we sadly watched the gallant attempts by the pilot to maneuver the stricken aircraft toward a suitable site for a crash landing, but the C-130 hit some trees and the subsequent fire ignited the artillery munitions loaded on pallets inside the plane for the air drop. Later that night we heard and felt the US Air Force retaliating with B-52 strikes that caused secondary explosions to the south of our position. For a detailed account and photographs on the shooting down of this C-130, see the links at (description) http://www.spectrumwd.com/c130/articles/aluoi.htm and (series of photographs of the crash) http://www.vhfcn.org/alouix.html |

|

|

|

| Damaged C-130 flying a low level S.E. to N.W. along the Valley Axis Just south of the southern end of LZ Stallion airstrip. The rear ramp is down. |

Note the battle damage to the fuselage, position of the control surfaces,

fuel streaming from the left wing, and the abandoned NVA Bulldozer in

the foreground. |

|

||

| Impact |

|

|

||

There is a story attached to the above photo. There was a network news team who were in the process of making a comprehensive report on Bravo Company, but when they observed the shooting down of this Chinook on LZ Cecile, they quickly lost interest in us and hightailed it out of the A Shau Valley as fast as they could. As an example of rapid battlefield promotions during a single day, one of our troopers started off in the morning as pointman, then he became the fire team leader, and by the end of the day he was the squad leader. |

||

|

During the A Shau Valley operation, the 1st Cavalry Division was confronted with the heaviest enemy air defense ever encountered in airmobile operations and the weather often aided the enemy. On many occasions, extremely poor visibility compelled our pilots to use flight paths underneath the clouds and NVA antiaircraft gunners exploited this by concentrating their fire on helicopters using these flight paths. Extraction from the A Shau began on 10 May with elements of the 3d Brigade, while the remaining 1st Cavalry Division units continued offensive operations in the Valley until the end of Operation Delaware on 17 May. The A Shau Valley had not only served as a sanctuary, but also as an extremely important supply depot for NVA forces. According to General Tolson, “one of the greatest intangible results of this operation was the psychological blow to the enemy in discovering that there was no place in Vietnam where he could really establish a secure sanctuary. The enemy had always considered the A Shau Valley to be his personal real estate and it was a symbol of his relative invulnerability. Operation DELAWARE destroyed that symbol.” |

||

Dropdown menu by http://www.milonic.com

http://www.milonic.com/removelink.php